by Dofinn-Hallr Morrisson and Thóra Sharptooth

Anglo Saxon Lyre. Anglo Saxon Lyre. Making Musical Instruments Homemade Instruments Music Instruments Cigar Box Guitar Mountain Dulcimer Hurdy Gurdy.

Copyright (c) 1992, 1995 Greg Priest-Dorman and Carolyn Priest-Dorman.

This document is provided as is without any express or implied warranties. While every effort has been taken to ensure the accuracy of the information contained, the authors assume no responsibility for errors or omissions, or for damages resulting from the use of the information contained herein.

- New Listing EARLY MEDIEVAL ANGLO SAXON FINGER RING-DECORATED-METAL DETECTING FIND. Time left 6d 13h left. From United Kingdom +$10.79 shipping. Watch; STUNNING ANGLO SAXON GOLD & GARNET PENDANT - CIRCA 6th/7th Century AD (988) $2,295.00. From United Kingdom.

- The Anglo Saxon Lyre Project. THIS SITE HAS BEEN SET UP TO PROMOTE AND DISEMINATE INFORMATION ABOUT THIS RARE AND BEAUTIFUL INSTRUMENT THAT NEARLY VANISHED FROM OUR CULTURE. IT IS INTENDED AS A POINT OF REFERENCE FOR ANYONE WHO HAS ANY KIND OF INTEREST, NO MATTER HOW SMALL OR LARGE, IN THIS MUSICAL INSTRUMENT OF OUR 'ENGLISC' PAST. IT WILL DEAL WITH THE INSTRUMENTS HISTORY, CONSTRUCTION, PLAYING TECHNIQUES, PHOTOGRAPHS, SOUNDFILES AND YOUTUBE POSTS.

Permission is granted to make and distribute verbatim copies of this document for non-commercial purposes provided the copyright notice and this permission notice are preserved on all copies.

This is an expansion and correction of a class pamphlet Dof has used at various East Kingdom University sessions.

The authoritative version of this document exists at http://www.cs.vassar.edu/~priestdo/lyre.html.

$Id: lyre.html,v 1.3 1995/12/27 12:26:45 priestdo Exp $

The lyre, a particular type of stringed instrument, has provedenduringly popular in many parts of the world. In northern Europe theGermanic tribes played a type of lyre called in Old English thehearpa. Mentioned in Beowulf, the lyre may have been theinstrument to accompany the performance of Anglo-Saxon poems andstories such as Beowulf. The remains of several such 'Germaniclyres' and their bridges have been found in Saxon and Frankish gravesin Germany and England; they range in date from the fifth through thetenth century (Crane, 10). The most famous is no doubt the one from the Sutton Hoo excavation, currently dated to the early seventh century. Sufficient information exists about the Saxon lyre to permit reasonable reconstruction and play of the instrument, and that is the subject of this article.

Playing the Lyre

From the earliest times, depictions of lyres fall into two categories: those with seven or fewer strings and those with eight or more strings. Consistent across 3,000 years of depictions of people playing lyres are two playing styles. Those lyres having seven or fewer strings are depicted being played in a fashion I will describe later that I call 'block and strum.' Those with eight or more strings are depicted with each hand separately plucking the strings, much as harps are played to this day.

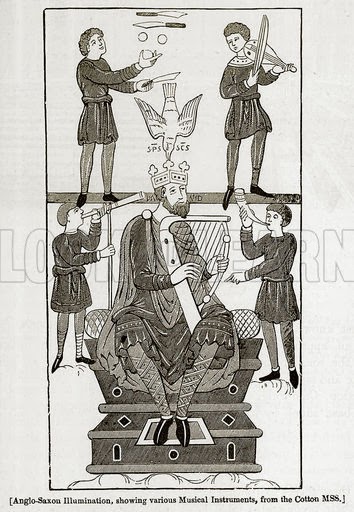

Several early medieval illuminations depict people playing lyres withseven or fewer strings. Eliminating those depictions that post-datethe time when the lyre seems to have been common (that is, depictionsfrom after the eleventh century) on the assumption that the artist hadnever seen someone actually playing the instrument, and focusing onthose illustrations actually contemporary in age with the finds, onecan see that there is great consistency in the way the instrument isheld and the way the hands are placed on the instrument. The lyre isusually held upright resting on one or the other leg; the left hand isbehind the instrument with the fingers spread, apparently against thestrings. The right hand may hold some kind of plectrum. In thosecases where there is no plectrum, the right hand appears to bestrumming the strings backhanded, which would result in striking withthe fingernails. Typical of these is the illumination of King Davidfrom the Vespasian Psalter (circa early 8th century); see Figure 1 for a redrawing of this illumination.

While the individual musician could have done any number of things possible on the instrument, the most likely way to play seems to me to be 'block and strum.' By this I mean strumming across the strings, either with the back of the hand or with a pick held in the front (usually right) hand, while at the same time blocking selected strings from behind with the back (usually left) hand so the strings you are touching with the back hand do not sound. This is very comfortable to do and produces pleasing results. It matches the arm, hand, and wrist positions in the illuminations and allows for comfortable support of the instrument.

Additionally, of the finds that have openings in the back of discernible size, the openings are longer than one half the string length. This would allow the left hand to produce half-length harmonics for occasional highlights. To do these you would pluck the individual string, which is the way I think plucking would be used occasionally.

We do have a statement contemporary with the instrument's usementioning how it was tuned, and an example of at least one piece ofmusic for it. Hucbald's De Harmonica Institutione (ca. 880)contains discussion and an illustration of lyre tablature for thecommon 6-string lyre along with tuning information. Hucbald isexplaining the work of Boethius, and gives his audience an example ofhow Boethius' musical system would describe their lyres. ThusHucbald's examples are descriptive rather than prescriptive of thetuning found in his day. He notes that intervals between the stringsof the lyre are tone-tone-semitone-tone-tone (Hucbald, 22-23). In modern notation, that tuning maps to C-D-E-F-G-a, or D-E-F#-G-a-b, these being the first six notes of a major scale or, looked at another way, the last three and first three notes of a major scale, or the last note followed by the first five notes of a Dorian scale.

Selecting Strings for Your Lyre

The following recommendations for strings are based on standard guitar strings, which are readily available in music shops. Steel strings are louder than nylon; however, steel puts the instrument under greater pressure than nylon. Use steel strings if you choose to build Option 1, and nylon if you choose to build Option 2. Option 1, having a plywood belly and back, benefits from the louder steel strings. Option 2, having a single-grained belly and the routed-out back, has a louder box and can make use of the nylon strings that sound closer to the sound of gut strings. If you find a cheap source for 'gut,' use those.

The following specifications are based on a measurement of 20' from tuning pin to bridge and approximately 30' overall instrument length. If the distance between your tuning pins and bridge is longer than 20', use slightly lower tunings; if the distance is shorter than 20', use slightly higher tunings.

To buy steel strings, ask for one each of strings 024, 020, 017, 015, 013, 011. These numbers refer to gauge. On your lyre, tune the lowest string to C or D.

To buy nylon strings, ask for two each of strings G, b, and e. On your lyre, tune the lowest string (a G string) up to b, resulting in a tuning of b-flat-c-d-e-flat-f-g.

Anglo Saxon Musical Instruments

Building Your Saxon Lyre

It is not the goal of this section to describe how to build a reproduction of an actual historical lyre. The best two authors to go to for information if you wish to build a reproduction of a historical lyre are Crane and Bruce-Mitford. This section tells how to make a hybrid lyre using modern tools and construction methods for the sake of getting one into your hands so you can learn how to play it. I would love to see people constructing their lyres in the way we believe medieval lyremakers to have constructed theirs, but that is another article.

I suggest you build your first lyre one of two ways:

- Using power tools and a simple design not exactly like the period examples; or

- Using power tools and a design representing a combination of the finds.

Figure 2 shows the nomenclature and component parts of this type oflyre. Figures 3 and 4 and their associated tables summarize the knownphysical evidence for extant lyres of this type. Look over theevidence and the other illustrations, read over the two methods, andthen pick Option 2 if you have some skill with a router, Option 1 ifyou don't. A high estimate of the cost of materials cost is under $50(1995 wood prices, USA).

Option 1

This lyre is made of a strong hardwood internal framework (the body) glued between two layers of thinner wood (the back and belly). It has a large hole through it across which the strings are strung (the handhole). See Figure 5.

Tools Required:

- Jigsaw or sabre saw and wood blade (If you are using a sabre saw instead of a jigsaw you will also need a small coping saw for cutting out the bridge and tailpiece.)

- Drill; bit for starter holes for saw, bit for tuning pins (usually 3/16' works for zither pins), bit for peg at bottom of lyre, small drill bit for holes for violin strap, tiny bit for string holes in tail piece

- Sanding device(s) of your choosing

- Clamps, clamps, clamps (or at least some bricks and boards)

Materials Required:

- Hardwood, oak or maple, for the body (see chart for size). (This can be a piece of joined wood. I have used maple shelves, available at many home centers.)

- Small piece of hardwood about 1/4' thick for the bridge and tailpiece

- Hardwood dowel for end peg--3/8' diameter is good, about 2' long

- Cheap 1/4' 3-ply paneling for the belly and back (Make sure there is a clear area between any decorative grooving in the paneling as wide as your lyre is going to be to get what you want.)

- Metal tuning pins (get a few extra for testing hole size); you can use zither pins or piano pins.

- Violin end peg strap

- About 100 small brass brads or round headed tacks, nails, etc.

- Wood glue

- Boiled linseed oil, a small clean glass jar, and rags for finishing

- Tuning key to fit the pins you got (they are not all the same!)

Construction of Option 1 Lyre

- Using the information in the figures and tables, and the wood available to you, make a pattern for your body, including the hand hole and sound box. Transfer the pattern to your piece of hardwood.

- Cut out the body of the lyre. Then cut out the hand hole and the sound box from the body. The resulting piece is the supporting framework for your lyre.

- Check your lyre framework against your pattern. If it differs, trace the framework onto another piece of paper and do all subsequent steps using this new pattern.

- Mark and cut a back and belly out of paneling. Do not cut out the handhole yet.

- Sand the entire framework. Be careful not to round the two surfaces to which the back and belly will be glued. Put a mark in the dead center of the outside of the bottom edge for the end peg. This will also help you tell where the handhole is to go later.

- Using wood glue, glue the back and belly to the body. Clamp it well and let the glue dry completely (usually overnight).

- Cut out the hand hole in the paneling. If you have forgotten which end is the hand hole end, look for the mark for the end peg.

- Continue as outlined below in 'Options 1 and 2.' Include all the instructions listed in parentheses.

Option 2

The differences between making this lyre and the one above are

- using a router to make the sound box so there is no bottom board

- using a better quality (not ply) wood for the top board

- using extra pieces of wood with the grain running in a different direction to reinforce the area around the tuning pins

Tools Required:

- Router and bit (I recommend a 3/16' or 1/4' cut diameter straight bit.)

- Jigsaw or sabre saw and wood blade (If you are using a sabre saw instead of a jigsaw you will also need a small coping saw for cutting out the bridge and tailpiece.)

- Drill; bit for starter holes for saw, bit for tuning pins (usually 3/16' works for zither pins), bit for peg at bottom of lyre, small drill bit for holes for violin strap, tiny bit for string holes in tail piece

- Sanding device(s) of your choosing

- Clamps, clamps, clamps (or at least some bricks and boards)

Materials Required:

- 1/4' hardwood panel for belly, tuning area supports, bridge and tail piece

- 4/4 hardwood (see chart for size) for body

- Hardwood dowel for end peg--3/8' diameter is good, about 2' long

- Metal tuning pins (get a few extra for testing hole size); you can use zither pins or piano pins.

- Violin end peg strap

- About 50 small brass brads or round headed tacks, nails, etc.

- Wood glue

- Boiled linseed oil, a small clean glass jar, and rags for finishing

- Tuning key to fit the pins you got (they are not all the same!)

Construction of Option 2 Lyre

- Using the information in the figures and tables, and the wood available to you, make a pattern for your body and a pattern for your reinforcing pieces.

- Cut out the body of the lyre from the 4/4 hardwood.

- Rout out the sound box from the body to a depth of 3/4'. You may have to do that in steps depending on how strong your router is and how good you are at using it. It's better to take it down 1/4' at a time than to go through the side accidentally.

- Leave a wide enough section of unrouted wood down the center of the cavity to support the plate of your router while you do the rest of the routing. Then take a 3/4' thick block of wood and screw it to the bottom of your router plate; this will allow you to remove that center section of wood while only one edge of your router plate is supported on the edge of the lyre. If your lyre is more than twice the width of your router plate, you will have to leave two sections of unrouted wood in the body of the lyre.

- You can inset the back tuning reinforcement rather than simply attaching it to the back. If you wish to do that, use your router and do it now. Only do this on the back of the lyre! To do this, turn your lyre over and rout out a section the depth of your panel and the height of your reinforcement piece.

- Cut out the hand hole from the body.

- Cut the belly piece out of the panel to match the body, not including the tuning pin area (see Figure 6). Leave the hand hole area solid for now.

- Cut two pieces from the panel with their grain running as shown in Figure 6. These are the reinforcements for the tuning pin area.

- Sand the entire body. Be careful not to round the surfaces to which the belly and reinforcing pieces will be glued.

- Glue the belly to the body, clamp, and let dry completely.

- Glue the tuning area supports to the body, one to the back and one to the front. Clamp and let dry completely.

- Cut out the hand hole section from the belly.

- Continue below, under 'Options 1 and 2.' Do not include the instructions listed in parentheses.

Options 1 and 2

- Using a scrap of the wood from which you cut out the body, drill a hole slightly smaller than a tuning pin. Hammer a spare tuning pin in with a few strokes to test the hole size. Use a small piece of scrap hardwood as a buffer between the hammer and the pin. If the hole is the wrong size, experiment until you find the right size drill bit.

- When you have found the correct size drill bit, lay out the holes for the tuning pins in the lyre. Spread them out across the top as evenly as possible: see Figure 2. Mark and drill the holes straight down--at right angles--into the surface. You can use a drill press for this step if you have one, but it is not necessary.

- As with the tuning pins, test the drill bit size for the end peg in a piece of scrap hardwood before drilling the hole for the end peg in the lyre. You want a snug fit. Put a mark in the dead center of the outside of the bottom edge for the end peg. Drill the hole for the end peg approximately 3/4' to 1' deep. This hole should also be at a right angle to the surface.

- Using your choice of the two patterns in Figure 4, cut out, shape, and sand the bridge. Gently round and smooth the surface where the strings will rest on the wood. Do not worry about cutting grooves for the strings; the strings will most likely seat themselves in the appropriate places when the instrument is strung.

- Using the pattern in Figure 7, cut out, shape, and sand the tail piece.

- Using the small drill bit, drill the two holes for the violin peg strap in the tail piece. Note that these two holes are drilled at an angle; see the cutaway view in Figure 7. If you wish, you may countersink the two holes on the top side of the tail piece in order to allow the metal ends of the violin strap to seat more firmly.

- Using the tiny drill bit, drill the holes in the tail piece for the strings.

- Sand, sand, and sand everything some more; it's not documentable, but it sure feels nice. This is your last chance to clean up all the edges around the instrument.

- Glue in the end peg.

- Using boiled linseed oil and a lint-free rag, oil all the wood, including the bridge and tail piece. If you can slightly warm the linseed oil, it will penetrate much better. Warming a small jar of oil in hot water works well. It's a pain to get to the area under the strings once the lyre has been strung, so repeat until the (cheap back and) belly wood have soaked up a few coats of oil. Please read carefully all instructions about working with linseed oil and disposing of your rag.

- Nail down the belly and either the back, for Option 1, or the back tuning pin reinforcement, for Option 2, to the lyre with the brads, spacing them evenly around the entire perimeter of the lyre at approximately 2' apart and approximately 1/4' from the edge. Nail around the hand hole also. (Be careful to offset the brads on the belly and back sides slightly so you don't try to hammer a brad into another brad from the other side.)

- Again using a small piece of scrap hardwood as a buffer between the hammer and the pin, hammer the tuning pins into the lyre with a few strokes. Hammer until the hole in the pin is between 1/4' and 3/8' above the body of the lyre.

Stringing and Tuning the Lyre

- Put the violin strap on the tail piece. Unscrew one of the two metal ends of the violin strap. Thread the strap through the two holes for it at the end of the tail piece. If you countersunk those two holes, the metal ends should fit into them neatly. Screw the metal end back on, making sure the two metal ends are on the upper side of the tail piece.

- Put your strings in the tail piece. If your strings have little lumps attached at one end, then you will need to string each one through the tail piece such that the little lump is on the underside of the tail piece. If your strings have no attachments, then you will need to string each one through the tail piece and then tie each end in a knot (see Figure 7) on the upper side of the tail piece. The lowest (thickest) string should be at the dexter side of the lyre; the strings work toward the highest (thinnest) string at the sinister side of the lyre.

- For this next step, if you don't already know how to string a musical instrument, call in a friend who does to help you. Place the violin strap around the end peg of the lyre. Straighten out the tail piece and bring the free end of the dextermost string up to the dextermost tuning pin. Put the end through the hole in the pin. You want to end up with two or three wraps of wire around the pin when you are done. Do not fully tighten the strings yet; after all, the bridge isn't even in place. Wind the pins clockwise.

- Once all the strings are on the lyre, slip the bridge into place under the strings. If the strings are too tight to let you do this, loosen them up a bit. Place the bridge approximately halfway between the bottom of the handhole and the bottom of the lyre. See Figure 2.

- Now carefully tune the lyre. If you are tuning it for the very first time, and you are using steel strings, you will need to tune the instrument down about one full step from the tunings recommended above. The reason for this is that the wood needs to adjust to the unfamiliar pressure of its new life. With both steel and nylon strings you must be patient: the strings will not keep in tune for long when they are new. Once the strings stretch in, they will keep in tune. Until then, expect the lyre to go out of tune rapidly.

Watch the bridge as you tune the lyre for the first time; it may try to pull forward or back a bit as you tune. Just gently straighten it out with your fingers.

Now play! The lyre may buzz for the first few days. If it continues to buzz after it has been strung for several days, first check the area around the tuning pins and make sure that none of the string ends are touching any other strings. You can trim any excess string ends down to about 1/2' if you like. If the bridge is the source of the buzzing, see if one of your strings is hitting the bridge in more than one place. If so, you will have to loosen the stringing on the instrument, remove the bridge, and carefully remove some wood from the bridge so that the string only hits the bridge at one point. Make very sure the surface of the bridge is smooth before you replace it under the strings.

Sources

- Babb, Warren, trans. Hucbald, Guido, and John on Music: Three Medieval Treatises, ed. and introd. Claude V. Palisca. Music Theory Translation Series, 3. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1978.

- Bruce-Mitford, Rupert and Myrtle. 'The Sutton Hoo Lyre, Beowulf, and the Origins of the Frame Harp.' Antiquity, XLIV (1970), pp. 7-13, Plates I-VIII.

- Crane, Frederick. Extant Medieval Musical Instruments: A Provisional Catalogue by Types. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1972.

- Diagram Group. Musical Instruments of the World: An Illustrated Encyclopedia. New York: Facts on File Publications, 1976.

- Hall, Richard. The Viking Dig: The Excavations at York. London: The Bodley Head, 1984.

- Hucbald, of Saint Amand. De Harmonia Institutione,trans. Babb.

- Montagu, Jeremy. The World of Medieval and Renaissance Musical Instruments. Newton Abbot, England: David & Charles, 1976.

- Page, Christopher. 'Instruments and Instrumental Music before 1300,' pp. 445-484 in The Early Middle Ages to 1300, ed. Richard Crocker and David Hiley. New Oxford History of Music, II. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

- Panum, Hortense. The Stringed Instruments of the Middle Ages: Their Evolution and Development, rev. ed. Jeffrey Pulver. Norbury, England: The New Temple Press, 1939; reprinted 1971 by Da Capo Press.

About the Authors: Greg and Carolyn Priest-Dorman, priestdo@cs.vassar.edu(NoSoliciting!), http://www.cs.vassar.edu/~priestdo/) both work at Vassar College, where they are allowed to use the library. Dofinn-Hallr Morrisson and Thóra Sharptooth live on a stead outside the teeming metropolis of Jorvík, tending the land and making things out of things.

It was not that long ago (1970′s) when writers were expressing doubts about what musical instrument was meant by hearpe in the Old English literature. The question was ‘Why have only two been found?’ (Grose & McKenna, Old English Literature, 1973). A few years later the question required no answer, because by then there was evidence of at least 15 hearpes, from various sites in England and Germany, all similar to the Sutton Hoo hearpe.

This early musical instrument, called by the Anglo-Saxons a hearpe, is what we call today a round lyre. The triangular frame-harp came into use much later in the Anglo-Saxon period.

This pan-Germanic hearpe or lyre, the most famous example of which is the Sutton Hoo harp, is the musical instrument associated with the early Old English poetry, such as Beowulf. It is a simple yet very elegant musical instrument; aesthetically pleasing in its rounded shape.

This six-stringed instrument, light in weight and not too large in size would have been easy for the travelling scop to carry from place to place. The hollow sound-box looks alarmingly shallow, being no more than 25mm in the case of the Sutton Hoo harp, but it can produce a sound appropriate in volume for the germanic mead-hall.

Tuning

The wooden tailpiece at the foot of the hearpe, which restrains the strings, need not be much more than 50mm long, in order that the bridge may be moved to a position that will give the strings a vibrating length of about 575mm. This should give the sound a reasonably low and full tone, and, particularly when tuned to a suitable pentatonic scale, the compass of the instrument will lie within the normal tenor register. Because of the nature of the construction of the hearpe, it will in most cases go out of tune much quicker than most other instruments. This tendency can be avoided by making sure that the strings are held firm enough at the base and in the pegs. The hearpe should then remain in tune without the need for adjustment for some weeks.

Hucbald

Information regarding the tuning of a six-stringed lyre is to be found in a work entitled De Harmonica Institutione (c 880) written by Hucbald (c840-930) who was a Flemish monk. This tuning, when starting from the first note of the C major scale, comprises the first six notes of that scale, namely CDEFGA.

However, Hucbald is not describing, or providing, any information on, the tuning of the Anglo-Saxon or Germanic hearpe. Hucbald is explaining how the Roman philosopher, Boethius (480-524) would havge tuned the classical lyre; an instrument which, as Hucbald notes, additional strings were often added to accomodate the ranges of the various modes.

Whether the Anglo-Saxon scop tuned his harp to Hucbald’s scales later in the Anglo-Saxcon period is not known, but certainly in the pagan period the scop would not have been familiar with the modes used by Boethius.

The Pentatonic scales

It seems fairly certain that the Anglo-Saxon hearpe would have been tuned to a pentatonic scale. The notes of these scales lie naturally to the musical ear between the octave and the instrument has six strings, which gives the five notes of the scale plus the octave note.

Pentatonic scales are very common throughout the world, being much used in the early folk music of various countries.

Any scale comprising of five different notes may be termed ‘pentatonic,’ but there are a number of early forms of pentatonic scales. The G flat major pentatonic scale is the base of melodies that may be played using only the black notes of the piano. The scale C D E G A (c), is the scale used in the early music of China.

The minor pentatonic scale, C Eflat F G Bflat (c), is the scale used in Appalachian folk music and it is also the scale used in early English folk-song music. Tuned to this scale, quite a number of early English folk melodies may be played on the Anglo-Saxon hearpe. Because these early English folk-song melodies go back many centuries, it is I think reasonable to assume that the Old English Scop would have tuned his hearpe to this pentatonic scale. We can therefore, I believe, bring back to life the sound of the Sutton Hoo harp.

Techniques

The main problem that remains is how was the hearpe played? Did it involve, as some have suggested, a technique called ‘block and strum? The problem with this technique is, if carried out for any length of time, it becomes very tedious to the ear. It is, I think, worth examining the Old English literature to see whether there is any mention of technique whilst playing the hearpe.

There is a late reference to ‘singing to the harp,’ that is Old English salletan (The Paris Psalter 104). But this term can also mean ‘to sing psalms’ (Latin psallere), and when sung with a harp it would have been the later triangular frame harp, such as is shown in the 11th century Psalter in St. John’s College Cambridge.

The Finnsburh Episode in Beowulf (Lines 1063-1065) seems to suggest that hearpe and song were conjoined:

∂ær wæs sang and sweg samod ætgædere

Fore Healfdenes Hilde-wisan

Gomen-wudu greted gid oft wrecan

(There was song and sound together gathered

before Half-danes battle leader

Game-wood played, tale often repeated) But sweg here may mean the general sound in the Hall, the background noise, rather than hearpesweg (the sound of the harp). This interpretation is perhaps strengthened by gomen-wudu greted coming in the next line; gomen-wudu (joy-wood) being one of a number of kennings for the hearpe.

A passage in Widsi∂ provides another reference to the joining together of hearpe and voice:

Donne wit Scilling sciran reorde

For uncrum sigedryhtne song ahofan

Hlude bi hearpan hleo∂or swinsade

When Scilling and I with clear voice

raised a song for our victorious Lord

Loud was the sound of the harp’s melody) In this passage Scilling is sometimes taken to be the name of Widsi∂’s hearpe rather than another person. But in either case it is not made absolutely clear that the hearpe and voice are heard together at the same time.

In The Gifts of men the hearpe appears to be played quite quickly and skifully and separately from the voice of the Scop:

Sum mid hondum mæg hearpan gretan

Ah he gleobeames gearobrygda list

(One with his hands may play the harp

He has on the glee-wood a quick-playing skill)

Note here also the term gleobeames (glee-wood), another kenning for the hearpe, sometimes appearing as gliwbeam. The late equation of this term with the timbrel (tambourine or drum) is either by extension or error. A play-wood or pleasure-wood, or perhaps music-wood, is the meaning of the term; the hearpe, basically, being a thin wooden board in appearance. The term gleo in the form glee, has come down to the present day, but now with the meaning part-song.

An extract from The Fortunes of Men describes a lively hearpe-playing style:

Sum sceal mid hearpan æt his hlafordes fotum sittan

feoh ∂icgan ond a snellice snere wrætan

lætan scrælletan sceacol, se∂e hleape∂

nægl neomegende, bi∂ him neod micel.

(One shall with hearpe sit at his Lord’s feet,

receive treasure and rapidly twang

the harp-string, letting the plectrum loudly sound,

which leaping nail sounds sweet

and brings much pleasure.) Here we see that the hearpe was, at least sometimes, played loudly and quickly leaping from one string to another.

Finally, some lines from the Riming Poem:

L 25 gellende sner (harpstring resounding)

L 27/28 scyl wæs hearpe

hlude hlynede, hleo∂or dynede

(clear-sounding was harp

loudly resounding)

Macrae-Gibson in his glossary (The OE Riming Poem, 1983) gives gellende, hlynede and dynede all as ‘resounding,’ but they must surely have had, at least, slightly different meanings. The sublety of meaning being lost means we have lost some information regarding the sound of the hearpe. Macrae-Gibson translates the lines as ‘ringing loudly so that the sound re-echoed;’ but this is a personal intepretation.

One thing to bear in mind is that, when the poetry is composed later in the period, it may well be that the references are to the triangular frame- harp rather than the earlier germanic round hearpe.

The Rhythm of the Poetry

Pope argues that the verse was rhythmically, rather than metrically, regular (J C Pope, The Rhythm of Beowulf, 1942 rev. 1966). He suggests that Old English verses ‘were chanted whilst being accompanied by a small harp which provided a drone.’ (ibid). However, the Old English extracts above do not support this suggestion. It does seem to be the case that, by slightly emphasizing the alliterated syllables, the natural rhythm of the poetry emerges.

Conclusions

We see from the Old English passages above that the hearpe was played in a number of different ways. It was played loudly, quickly, with leaping notes, sweetly and with a resounding sound. The technique was not restricted to a drone (though a sort of drone may be sustained if required), nor was it restricted to repetitive ‘block and strum,’ which soon becomes wearisome.

It is reasonable to assume that the hearperes would have had some differences in their techniques; there is no reason to assume that there was a standard method of playing the instrument. The hearpe would have been very useful during the recital of the poetry. It might have been played during short interludes, especially when the scop needed to collect his thoughts. It must surely have been used to reflect the various moods, actions and atmosphere of the poetry.

(Based on Article published in Withowinde, Spring 2005)

Anglo Saxon Culture And Values

August 31st, 2010